EXHIBITION ESSAY

Insistencia/Resistencia: 3 Contemporary Artists from Guatemala

13 May – 4 June 2023

Crafting histories and desires and angers

by Simon Soon

'Insistencia/Resistencia' showcases three art practices that intersect with craft and design, while delving into both contemporary and indigenous cosmologies that speak to pressing issues of cultural identity, displacement, and belonging in the context of Guatemala. The exhibition features artworks by three globally renowned Guatemalan contemporary artists: Marilyn Boror Bor, Antonio Pichillá Quiacaín, and Esvin Alarcón Lam. Each artist brings a unique perspective to the show by exploring the issues of cultural inheritance, as well as the role of art in addressing social change.

Marilyn Boror Bor is an indigenous artist who creates art inspired by Mayan culture and traditions. One of the main themes in her work is the preservation of knowledge and memory. She uses weaving as a medium to express this theme, as it is an important part of Mayan culture and is traditionally used to pass down knowledge from generation to generation.

Marilyn’s art often features motifs and symbols inspired by the flora and fauna in the landscape around her. By weaving these symbols into her work, she is creating a dictionary of memory that preserves the knowledge and traditions of Mayan culture. But blank spaces in the work stand in for the many species of plants and animals that have already gone extinct, or soon will be.

Marilyn Boror Bor, ¡ K’ O CHI NUK’U’X! Recuerdo

¡ K’ O CHI NUK’U’X! Recuerdo (Memory) (“Like memory in your heart”) consists of coloured patterned threads sewn onto a long sheet of paper folded into an accordion folio, a work made in collaboration with her mother. The sewn paper weaving here references the traditional codices of the Mayan people, only three of which have survived to give us a glimpse into pre-Columbian Mayan cosmology. Marilyn chose to weave on paper because she believes that stamping these memories onto paper allows them to be more easily preserved. The piece also features loose ends that can be combed, which is Marilyn’s way of encouraging future generations to continue the act of weaving.

Remembrance is a key theme in Marilyn’s art practice. In Diccionario de Objetos Olvidados (Dictionary of Forgotten Objects), she repurposes the dictionary as a knowledge system to record ordinary objects familiar to her community, as a documentation of shared contemporary experiences among the indigenous communities of Guatemala.

Marilyn’s work is deeply connected to her identity as an indigenous woman from the city of San Juan Sacatepéquez in Guatemala. Her hometown used to be known for its flower industry, but when cement companies moved in, the landscape and industry were drastically changed. Peinar las Raíces II (“Comb the Roots II”) is a powerful expression of how the threads of life seep into blocks of cement, the soft thread pushing through the solid matter, producing cracks in its hard surface and blooming like a flower amid the grey. The work evokes the flowers and changing landscape of Marilyn’s hometown and expresses her insistence on preserving her town’s history as a form of resistance against its erasure.

Marilyn Boror Bor, Peinar las Raíces II

Weaving is traditionally the domain of women in Mayan culture and a form of knowledge that they pass down across generations. In indigenous communities, the preservation of knowledge through symbols and colours is especially important due to the high illiteracy rate. However, Marilyn notes that many indigenous men no longer wear traditional clothing (demonstrations of Mayan weaving traditions), so it is up to women to continue this tradition.

Marilyn’s work is not just about preserving knowledge, but also about the connection between humans and nature. She believes that nature is as alive and important as humans are, and thus that it deserves to be treated with the same respect that we would give our fellow men. Her artwork is a way of continuing the conversation between humans and nature, and of reminding people of the importance of preserving the natural world.

Antonio Pichillá Quiacaín is an indigenous artist hailing from San Pedro, a town located near the picturesque Lake Atitlan in Guatemala. He speaks Tz’utujil, one of Guatemala’s 23 indigenous languages. After studying fine arts in Guatemala City for five years, Antonio returned to San Pedro, where he reconnected with his Indigenous identity through learning more about its language, textile traditions, and spirituality. His art is largely inspired by farming and weaving, which is what his father and mother respectively did to earn their living.

Antonio Pichillá Quiacaín, Kukulkán

Antonio’s Kukulkán (serpiente emplumada) features the snake motif which is central to Mayan cosmology. The Mayan calendar only has 20 days, and one of them is called Kan, meaning life. The Kukulkán snake in Antonio’s work is a symbol of life, slithering up and down just like life’s fortunes. that moves up and down like life. The snake’s shape is based on one found in the Madrid Codex, which Antonio has translated, with a contemporary spin, into a textile form. By doing so, he attempts to reinvent and re-present Mayan culture to outsiders, an endeavour that’s important to him since there are only three surviving Codices (in Madrid, Paris, and Mexico). (Incidentally, Antonio believes that these codices should be called “Codices in Madrid, Paris, and Mexico” instead of their current naming situation, and that they should be repatriated to the Mayan region.)

Antonio Pichillá Quiacaín, ABUELA

Antonio's second work, ABUELA (“Grandmother”), features woven ropes dyed blue, green, and white, with their loose ends bunched and tied together with brown cord. The work’s title references the primacy of women in passing down indigenous weaving traditions; each piece of traditional woven textile stands for a grandmother’s legacy passed down through the generations, for future generations. There are as many versions of a weaving like Abuela as there are actual abuela’s, as each woman adds a bit of herself to the tradition of weaving that she passes to the woman after her. In fact, Antonio even likens the process of weaving to giving birth; so symbolically linked are the two processes with ideas of legacy, posterity, and the future self.

Though not shown in the present exhibition, Antonio’s previous artworks that feature stones are also worth noting. For Antonio, like Marilyn, stones, like any other natural object, are living entities. He dresses up found stones in threads and fabrics, turning them into abuelo’s and abuela’s. His works visualise the process of weaving by showing the weaving in an incomplete state, with rough knots and loose ends, representing the work of women.

Antonio’s art seeks to reinvent the perception of Mayan culture and showcase the complexity and beauty of indigenous knowledge. In his practice, Mayan culture is more than just an object of study or an exotic artefact for touristic ogling; rather, it is a living, breathing, evolving thing.

The work of Esvin Alarcón Lam explores themes of identity, memory, and history through a range of mediums including sculpture, installation, and performance. In his work, Esvin seeks to challenge dominant narratives and address the absence of marginalised voices in public discourse.

One of Lam's most notable projects is Pagoda Imaginaria Residencia, which emerged from his experience curating a museum of the Chinese diaspora in Guatemala, centering Guatemala’s significant Chinese community. With Pagoda, Esvin sought to address the absence of public platforms for the Chinese-Guatemalan community to discuss their situation and their histories, and he organised the project with the help and input of many people. Despite the discomfort of some members of the Chinese community who wanted the museum to cater solely to their community, the event was successful in attracting a diverse audience.

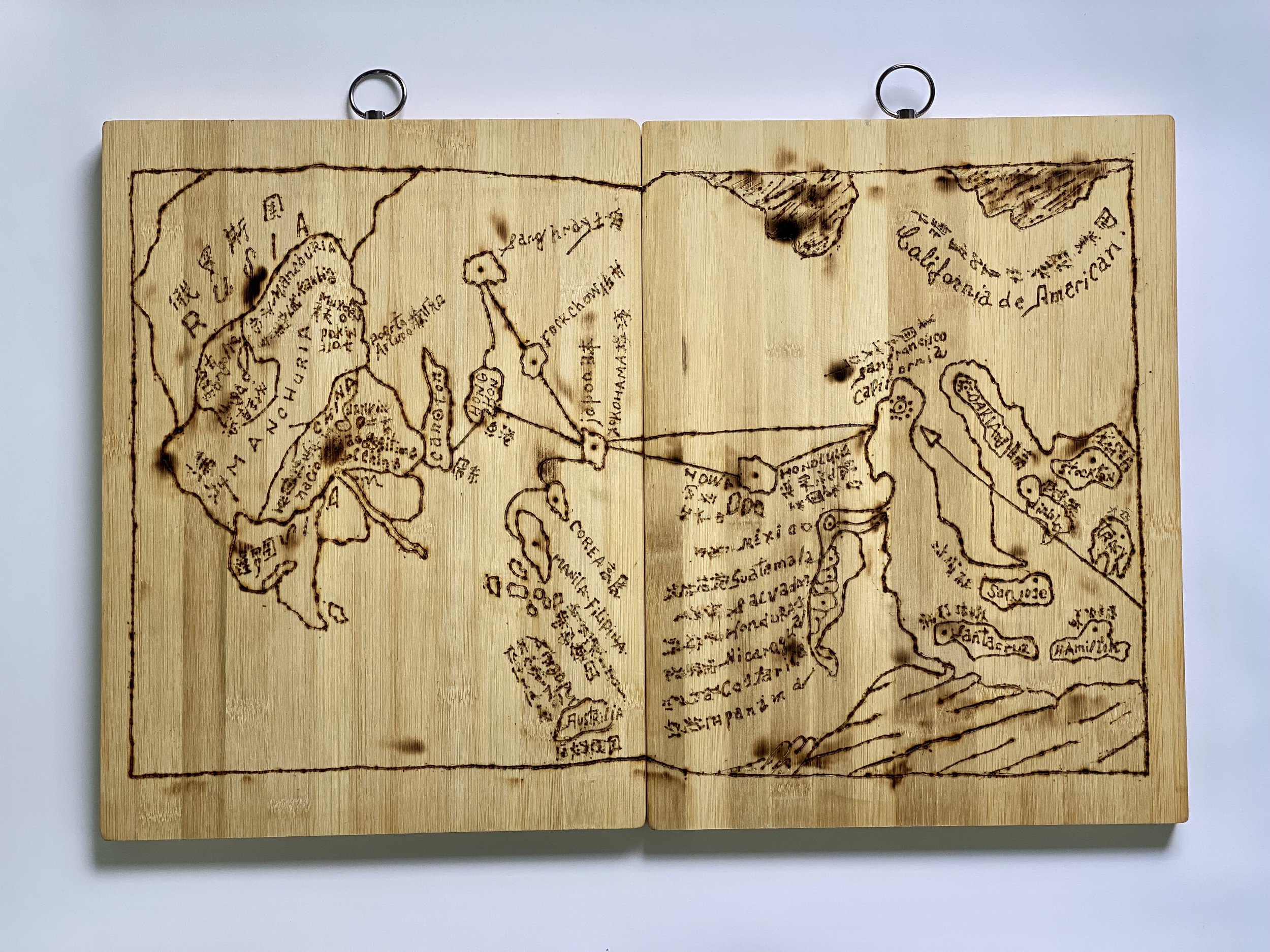

Esvin Alarcón Lam, A Manuscript of Oral Fixation No. 1

Materiality and the history of materials are prominent themes in Esvin’s map works. A Manuscript of Oral Fixation No. 1 is a hand-drawn map soldered on a wooden board. The map is based on a drawing created by a Chinese migrant doctor in Nicaragua. In close examination, the map does not conform to Western representations of the world, but instead offers a representation of a migratory route that tells the story of how Chinese people arrived in Central America by crossing the Pacific Ocean.

History and memory are also important themes in Esvin’s practice. In Guatemala, much of the history is oral, and stories are passed down through retelling. Since much of Guatemala’s history takes an oral form, Esvin wants his work to be approached like an open book, exposing Guatemala’s history to the world, along with the processes of erasure and ignorance that have accompanied it. His work highlights the political nature of memory and the painful consequences of its erasure.

Esvin Alarcón Lam, Inverted America (triptych)

Themes of displacement and limitation also appear in Esvin’s work, in regard to gender and sexuality as well as race. Inverted America, a triptych of three paintings that create a pattern out of triangles that symbolically stand in for Central, South, and North America (in the style of the symbolically-laden patterns of Anni Albers), challenges dominant narratives and highlights the acts of subversion that aren’t always obvious. In Guatemala, gender and race are not commonly discussed, but Esvin situates his work within these larger debates, shedding light on overlooked issues.

Though Esvin’s work is deeply political, he refuses to represent Guatemala or validate any fantasies or stereotypes about the country. He does, however, situate his work within larger political debates, particularly those related to race and gender. He rationalises his work by addressing the absence of marginalised voices, thereby challenging dominant narratives. Through his use of materiality and history, his exploration of memory and displacement, and his attention to gender and sexuality, Esvin sheds light on overlooked issues and exposes the erasure that occurs when history is ignored.

Insistencia/Resistencia proposes that visual forms make certain claims through their insistence that visuality makes certain demands through a creative retelling of mythologies, a process described by art critic Marian Pastor Roces as being ‘passionately [...] crafted out of histories and desires and angers’ that collectively shape a shared horizon of temerity. In doing so, the three artists in this exhibition derive inspiration from their personal experiences and the broader societal and cultural concerns that drive their artistic endeavours, in a nation grappling with entrenched racism. Through their work, they illustrate how visual art has the power to generate evocative and imaginative expressions that encourage dialogue and narrow the gap between Guatemala’s indigenous and non-indigenous communities.

About the Writer

Simon Soon is a senior lecturer at the University of Malaya in Kuala Lumpur. He researches across a range of interests in modern and contemporary art and architecture in Southeast Asia, further to completing a PhD at the University of Sydney which examined left-leaning political art movements in the region from the 1950s to 1970s. Simon is a co-founder and editorial advisor of SOUTHEAST OF NOW: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia, a peer-reviewed journal published by NUS Press and was one of the editors for Narratives of Malaysian Art, vol. 4. He is also one of the founding members of Malaysia Design Archive, an archival, research, and education platform on visual cultures of the 20th century. He also makes art, and has exhibited his work in Kuala Lumpur, Warsaw, Yangon, Hong Kong, Dhaka, Bangkok, Shanghai, and Manila.